Where did one of the architects of President Kennedy’s main program for Latin America, godfather of baptism from the Alliance for Progress, come from in 1961? In what hands did Ronald Reagan (1981-88) and George W. Bush (2001-2008) place their most important offices for the western hemisphere: those that coordinated the contra war in Nicaragua in the 1980s, and in the Department of State when the failed coup against Hugo Chávez in 2002? Who did Clinton and Obama pick for second place in the Defense Department bureaucracy toward the region? What led George W. Bush to choose his Commerce Secretary in his second term? What is the reason for President Trump’s proposal for the presidency of the Inter-American Development Bank?

The answers to all these questions have one ingredient in common: he is a Cuban-American. More exactly, one that is opposed to the Government and the prevailing economic, political and social order in Cuba.

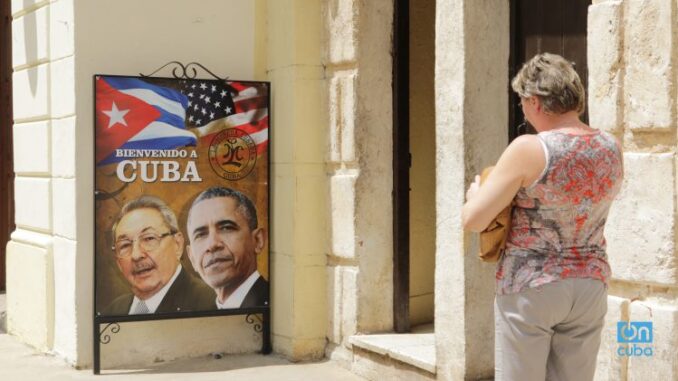

Now, if the US policy towards the Island is concerned, the question to be clarified would rather be to what extent the presence of Cuban-Americans in hierarchical positions within Republican and Democratic administrations proves that this policy is dictated by a pressure group implanted in Miami. Or seen differently, to what extent the command organs of that great power have been penetrated by some Cuban-Americans who share the same ideological fixation, with the evil purpose of “redirecting” it against the Cuban order.

The previous question could land on two questions: Is the appointment of the aforementioned decision-makers explained by the power of a Cuban-American lobby that represents historical exile? Is it up to these lofty Cuban-Americans to engage or directly influence Cuba policy? What history reveals is not so. Ernesto Betancourt, a former official at Banco Nacional de Cuba, was already a technocrat for the Organization of American States (OAS) when he was chosen by Kennedy’s advisers for the Alliance project. Otto Reich had served as a military, business consultant, and administrator at USAID ( US Agency for International Development) for the region when he joined the Oliver North team, survived the Iran-Contra scandal, and earned merit to be co-opted again by Republican diplomacy. Pedro Pablo Permuy and Frank Mora passed the revolving door that gives congressional staffers and professors from military universities access to inter-American positions in the Department of Defense, thanks to the ebb and flow of Democratic administrations. Carlos Gutiérrez was the CEO of the Kellogg (the one of the corn flakes) by being designated for Commerce by George W. Bush. Mauricio Claver-Carone held Treasury positions under that same Republican presidency, long before Donald Trump noticed him, not precisely for his anti-Cuban lobbying work in Congress, but during the electoral campaign in Florida, and invited him to the transition team in a Republican administration that had already raised the flag of reversing Obama’s policy across the line.

Certainly, in the selection of US government personnel to prevent “other Cubans” in the hemisphere, in the 1960s and 80s, anti-Castro anti-communist harvest must have had some weight in the curriculum of Reich and especially of Betancourt. Surely it was decisive when the director of Radio Martí had to be appointed in the period 1985-2000, or whoever co-chaired (with Condoleezza Rice) the sonorous Commission for Assistance to a Free Cuba , of which, by the way, it has not been heard from again. since 2006. In any case, they all served the government that employed them, not as representatives of any Cuban-American lobby.

Until the early 1980s, it never occurred to anyone to argue that Playa Girón, the multilateral embargo also known as a blockade, the October (or Missile) Crisis, the covert operations plan called Mongoose, the insurgency that unleashed a bloody war civil (1960-1965), the impunity of Omega 7, Alpha 66, CORU and other paramilitary organizations in the 70s or any of the other axes of hostility against the Revolution responded to the power of a Cuban-American pressure group. Rather, they were part of a policy of force, conceived, formulated and applied by the national security command bodies, articulated in the National Security Council., where the decisive levers of that relationship have resided since the beginning of the conflict, above any of the committees of Congress.

Leave a Reply